Last

year, I sat down at my guided reading table to work with

a group of very good readers. I usually have 4-6 readers at

my table. This particular group was 6 readers that could read at a level

L. As I opened the book up for discussion, there were great comprehension responses

to the texts that "wowed" me as a teacher.

However,

there was one student that remained fairly quiet. I dismissed

the other readers back to their seats and turned to the quiet student. I

asked him a simple comprehension question. He couldn't reply with an answer. I got that "deer

in the headlight" look. So, I decided I needed to zero in a little

closer with him to see if there was an issue with comprehension.

I listened to him read a portion of the text again and then

asked a few simple questions. He couldn't give me an answer although he

could read extremely fluently.

This

story replays often every year with fluent readers. They can

read anything you set in front of them, but cannot answer basic comprehension

questions. They have mastered the reading, but aren't

thinking about the story or comprehending what they

are reading.

To

be a good reader, students need to think about

what they are reading. This actually takes a skill that

sometimes has to be taught. Students know they need to string

letters together to make words, but sometimes they don't realize or

understand that these words together have meaning. It seems

simple enough to children when this comes naturally, but a few strategies

of reading comprehension will help those that this does not

come naturally.

Comprehension is thinking about

what you are reading.

There are several comprehension strategies

that can be used to help students or young children begin to think about what

they are reading. When introducing these strategies, I start with an

anchor chart. This is the big paper that can be made into large posters to hang

while you are studying a concept. I place

all of these on a comprehension wall that we refer back to over the course of

the school year. At the end of the year, students often beg to take them home as

souvenirs.

The strategies are taught for 2-3

weeks.

- Connections

Connections are when

you as the reader connect what you are reading to something else in your

life. Sometimes this is another book, text to text.

Sometimes, this is an event in your life, text to self. Sometimes this

is a connection to something in your world, text to world. Examples of

text to world are holidays, public events, or articles related to the book. When I taught 3rd grade, I taught each

of these connections for a week. Now

that I teach first grade, I usually linger on a strategy for 2-3 weeks.

- Background Knowledge also

known as Schema

Background knowledge is just simply what

your readers already know about a subject. Students may read a book about

a birthday party and understand the context because they have had a

birthday party or have been to a birthday party. Similarly, if they read

about a dog and have a dog, they will have schema or background knowledge

about dogs, the subject they are reading.

If students read about a wobbegong

and have never seen a wobbegong, they wouldn’t have a clue about

what they are reading, nor would I. I

had to look it up. No, seriously. I had to look it up.

In addition, I can’t

pick up a neurosurgery book and understand what I am reading. I would lose

interest pretty quickly because I don’t have the background knowledge for these

areas.

- Visualization

I teach this to young

students as 'a movie in your head.' We pop popcorn and drink

mini sodas. I set up a mini movie theater background and put it behind

me while I read a book. I don’t show them the pictures. I ask them what they are visualizing. I also give them a piece of blank paper and

have them draw what they are seeing in their head. I repeat the term visualizing

repeatedly to help them remember. I

might say, “What are you visualizing?” as they draw their pictures on clip

boards.

After the students

have completed their drawing, I show them the illustrations to compare.

Sometimes students have very similar ideas about what they are visualizing as

the illustrator. They love to compare

their drawing to one another as well.

- Inferencing

This skill is when

you know something about the book that isn't written in words.

For example, "My

sister hit me really hard. I turned and looked at her with a grimacing

face. My mom knew how I felt."

The text never says

she is mad or hurt, but you can inference this because

of the choice of words the author used. As adults you inference

when you read mystery novels or “who done it” books.

- Questioning

This strategy can be

taught by teaching students to ask questions about what they are reading.

Many times, we ask the questions and expect them to answer. We forget to have students ponder, or wonder

about their reading. Ask them what they wonder or if they have questions

about their reading. Give them time to think about their questions. Even if they come up with outlandish

questions or far-reaching questions, it is leading them in the direction of

thinking about what they are reading.

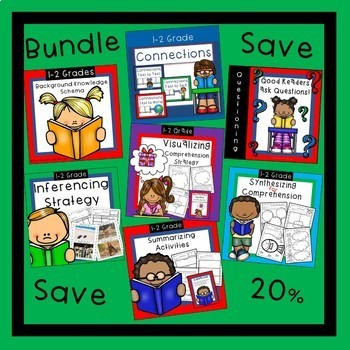

For more help or information to teach the strategies, click here!

👉 Reading Comprehension Strategies Bundle

Comprehending reading will open

new worlds of fun reading to your child or students.

For more information

or companions and printables that will help you teach these comprehension strategies,

visit at Robin Wilson First Grade Love on Teachers Pay

Teachers.com.

You can teach this with books that you read with your students or with your child. If you are interested, I have already created many book companions that follow this plan listed above.

Click on the pictures of these book companions that will help you teach comprehension strategies to save time.

No comments:

Post a Comment